This week marked the anniversary of the Battle of Lepanto on 7th October 1571, which still ranks as one of the major events in the history of the Mediterranean, and indeed around the world. The Ottoman fleet was defeated by the Holy League in what was the last sea battle to be fought by man-powered galleys. The date is important, as the beginning of the end for Turkish maritime supremacy in the European part of the Mediterranean. But what did it mean for the people living in and around the Adriatic at that time?

It’s telling that two very different poems were written in the 20th century about Lepanto. Firstly, G.K. Chesterton’s Lepanto written around the time of the First World War, with its well-known refrain “Don John of Austria is going to the war”. It’s extremely powerful, a rousing, evocative call to arms and you can almost hear the banging of the great drums urging the oarsmen onward. In total contrast, from 1984 comes Ljubo Stipišić Dalmata’s Kod Lepanta sunce moje (In Lepanto, my sun), a heartfelt lament for those brothers and husbands that never returned home. For those that did not die in battle, there was the worse shame of slavery, chained to oars aboard enemy galleys.

Hvar’s momento of the battle is a small wooden dragon on display in the Franciscan Monastery. Known as Zvir (the Beast), it was the prow decoration of Hvar’s galley, the San Girolamo, or Sv Jerolim in Croatian. It’s one of the few surviving relics of the battle, in which so many boats and lives were lost. There are plans afoot to build a replica of the Sv Jerolim, but in the meantime the Croatian Maritime Museum in Split has a model of her. The original was about 50 metres long, with 23/24 oars on each side, and a battery of 5 guns on the bow. She was commanded by Giovanni Balsi, and fought in the centre division alongside Don John himself.

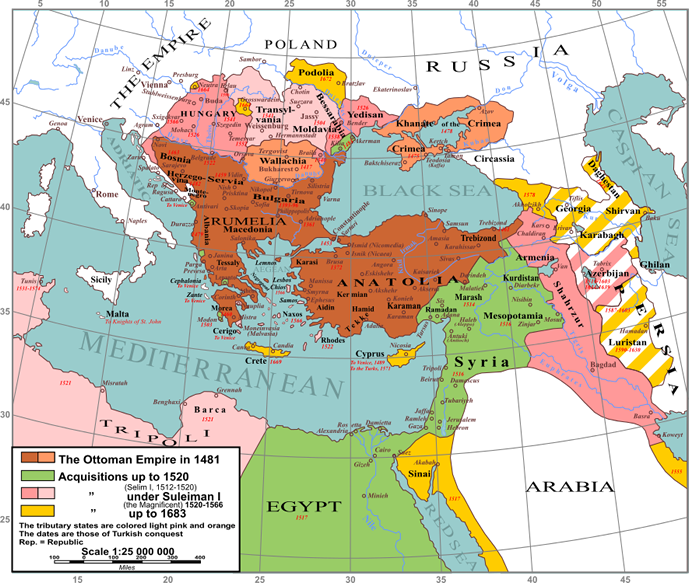

The year 1571 was not a peaceful one up and down the Adriatic coast. The Ottoman navy was on a mission to take over as many Venetian possessions as it could, and disrupt the others. Corfu had fallen, and further east, Cyprus was under attack. It was a war of commercial interests, and for harvesting slaves. For vessels driven by oars, the cheapest form of power was slaves. So any place attacked by Turks could expect to lose their menfolk, in addition to having their homes burnt down and any livestock taken.

The attack on Cypus was the last straw for the Venetians, who asked for help from Pope Pious V. This then became the final crusade, in which the Holy Alliance, consisting of Spain (including the Kingdoms of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia), the Republics of Venice, Genoa, the Duchies of Savoy, Urbino, Tuscany and the Papal States, all went to war against the Ottoman Empire. Much has been made of the Christian versus Muslim aspect of the struggle, but it really seemed to be more about commerce than religion, to be honest!

Unlike the Turks, and to some extent their Spanish allies, the Venetians still preferred to power their galleys with free men. It was more expensive, but as they didn’t keep their war galleys at sea in peacetime, they only manned them as needed. And the oarsmen were also very capable fighters, once they were able to catch their breath after a burst of full speed ahead! The Venetian contingent that set off to war included a number of galleys powered by fishermen, farmers and sailors from the Adriatic area. Venetian laws established the maximum number of oarsmen each town had to provide, and recruitment was by drawing lots, exempting some whose family members had already had died in battle. The names of the galleys and their commanders have both Croatian and Italian versions which were reported in the Venetian archives.

Croatian galleys in the battle of Lepanto

Left wing:

Cres: San Nicolò con la Corona (Sv. Nikola), commanded by Collane Drasa. Majority of crew killed so not able to sail home.

Veglia/Krk: Cristo Risuscitato (Uskrsli Krist), commanded by Lodovico Cicut. Majority of crew killed so not able to sail home.

Capodistra /Koper (Istria): Leona (Lav) commanded by Gian Domenico Tacco. Captured a turkish boat. Sailed home.

Centre division:

Lesina/Hvar: San Giralamo (Sv. Jerolim), commanded by Giovanni Balzi. Captured a turkish boat, sailed home.

Right wing:

Arbe/Rab: San Giovanni (Sv. Ivan), commanded by Ivan Dominis. Majority of crew killed so not able to sail home

Trau/Trogir: La Donna (Žena), commanded by Alvise Cippico. Sank in battle

Cattaro/Kotor: San Trifon ( Sv.Trifun) commanded by Bisanti. Sank in battle

Reserve division:

Sebenico/Šibenik: San Giorgio (Sv. Juraj), commanded by Kristofor Lučić. So badly damaged it sank after the battle.

Zara/Zadar: galley was not at Lepanto, having been damaged near Corfu during the recent clash

In addition, some 30 Dubrovnik merchant ships turned out in support of the allied fleet, though they didn’t participate in the actual battle due to that city’s independent status. Dubrovnik was the Switzerland of its day.

The combined Allied fleet assembled off the coast of Sicily in August of 1571. That unfortunately left the Adriatic wide open for diversionary attacks by some 80 galleys under the command of corsair (ie privateer) Uluj Ali. Following raids on Corfu, Kotor and Ulcinj, in early August they attacked Korčula, successfully pillaging the countryside for whatever they could take, but failing to take Korčula town itself. A timely bura (strong northeasterly) threatened to drive their boats on to the rocks, so they withdrew. By 17th August, they were attacking Hvar, burning the houses in the town while residents watched from the safety of the fortress above. Continuing round the coast, the Turks burned down Stari Grad and Vrboska, though had more trouble in Jelsa. The legacy of those attacks can still be seen in the fortified churches that were built to protect the villagers from further raids.

Uluj Ali, it turns out, was not himself a Turk, but an Italian from Calabria that had been captured and forced to work as slave labour in the Ottoman galleys. He did pretty well for a slave, working himself up to bey (Viceroy) of Algiers by the time of Lepanto. Having inflicted so much pain and suffering to Venetian possessions in the Adriatic, he withdrew to the fleet’s base at Lepanto.

Replica of the Don John’s flagship The Real, built in Barcelona in 1971 for the 400 year anniversary

Meanwhile in Sicily, the main allied fleet was preparing for battle. Logistically it must have been a nightmare, with so many boats, each one with a large contingent of men to be armed and fed. There were 206 galleys in all, with 6 larger galleasses carrying extra artillery. The fleet commander was one Don John of Austria, remarkably only 24 years old but apparently an excellent strategist. Over in Lepanto, the Ottoman navy was making itself ready – with 220 galleys, and 56 galliots (smaller, nippier boats).

In terms of manpower, there were around 68,000 on the allied side, and 84,000 on the Ottoman side. That’s an incredible number of people packed on to those galleys, many of whom were there involuntarily. It’s been calculated that at around 40% of those taking part in the battle would have been from what is now Croatia, between the mercenaries, freemen and slaves on both sides.

The battle plan and the analysis of the strategy makes very interesting reading, and you can find it on Wikipedia and other places. I won’t go into that here, other than to say that joining battle by rowing must unfold in slow motion. A fleet of galleys has to hug the shore, so there’s no real choice in positioning. The allied fleet going southwards came round a headland shortly after dawn to find the Ottoman fleet heading north, so they all lined up in opposing rows as previously planned and rowed deliberately forward in formation. Not until near midday were they close enough to exchange shots! Then until 4 o’clock in the afternoon they plugged away at each other with great loss of life on both sides. Hvar’s Sv Jerolim fought in the centre division, and managed to return home afterwards. Other galleys were not so lucky.

The Holy League lost around 7,500 soldiers, sailors and rowers dead, but they also freed about as many slaves from the other side. On the Ottoman side, casualties were around 15,000, and at least 3,500 captured. An incoming storm sent the surviving boats for the shelter of the nearest safe haven, leaving who knows how many people to die in the water. Battles are messy.

The Ottoman fleet lost their commander and all but 30 of their ships, of which 117 galleys and 10 galliots were captured in good enough condition to reuse. On the Allied side 50 ships sank, and one Venetian galley was the only prize kept by the Turks, as they abandoned any others in the storm.

In the aftermath, the captured Venetian galley and their observations of the larger galleasses led to subsequent improvements in the Ottoman fleet and they continued to harass coastal towns on the Adriatic for many years. The following winter was particularly bad, leading to considerable hardship for a people depleted of so many of their adult male population, and hit by plague and famine. The Turkish corsairs continued to operate, while Venice dealt harshly with any locals attacking Ottoman trading ships. Yes, the battle of Lepanto was a huge victory for the Holy League, but I’m not sure the effects of that were appreciated by the people of the Adriatic.

Here’s Kod Lepanto, sunce moje sung beautifully by Klapa Puntari at the Omiš festival in 2011

Below are the words of Ljubo Stipišić Dalmata’s song, who also wrote the music. And alongside, my best attempt at translating the Dalmatian dialect to give the same feeling. Thanks to Miki Bratanić for clarifying some of the meaning for me. I hope I got it right!

| Kod Lepanta sunce moje | At Lepanto, my love |

| Braćo,sestre! Čorne visti donosimo sa Levanta: Osan galij ‘z naših misti suprostiva turskin brodin. |

Brothers and sisters! Black news we bring from the Levant: Eight galleys from our place against the Turkish fleet. |

| Sa Levanta vaših muži jauk neće nan doplutat; i veslačin i puntarin bojovnicin greb u škunan. |

From the Levant your husbands cries will not reach us; and oarsmen and soldiers are buried in their ships. |

| Kod Lepanta,sunce moje, kod Lepanta,kod Lepanta, sunce moje,utopi si tilo, tilo jako. |

In Lepanto, my love, In Lepanto in Lepanto My love, your body is drowned, your strong body. |

| Kod Lepanta u bojevju, kod Lepanta,kod Lepanta u bojevu galijunin. Turci,Turci bisni. |

In Lepanto in battle, In Lepanto In Lepanto in the battle of the galleys. Turks, raging Turks. |

| Plač’te brate,žene muža tujin dnima mladost njina; koj’ priživi,višje srama, veselu tujen obverigan. |

Lament women for your brothers and husbands, Their youth is taken by someone else; who survives has worse shame, chained to foreign oars. |

| Di van poja mašklinana, siročići išću čaču !? Zemjo stoput potakjana, tila stoput uskrisana. |

In the abandoned fields, orphans seeking their fathers!? Land a hundred times staked, bodies a hundred times resurrected. |

| ‘Oće l’ more igdar dovuć’, ‘oće l’ more,’oće l’ more igdar dovuć tvome mistu kosti,kosti bile? |

Will the sea ever bring will the sea, will the sea ever bring to your place bones, white bones? |

| Ol’ će more mene odvuć’, ol’ će more,ol’ će more mene odvuć dolin u tve dvore, dvore smirne? |

Or will the sea pull me will the sea, will the sea Pull me down to those halls Quiet halls? |

Read more…

Croatian Maritime Museum, Split

Wikipedia Ottoman-Venetian War (1570-73)

Hvar’s Galley St Jerome by lesignan – Maristella

Fešta forske pulene” 2014 – Exhibition16.6.2014 – 19.6.2014 Hvar

Battle of Lepanto 1571 and the Venetian Eastern Adriatic Impact

Hi Mara,

I want to compliment ánd thank you for this fantastic peace of research.

Always searching for historic references and details, I simply love stories like you wrote.

And not only for me, but for any visiting tourist with slightly more interest than just for another wine and a pizza, this is great info to get to understand Croatia’s role in history.

With my (slightly limited) knowledge of English, and poor Croatian, such detailed work is a bit to much for me, so thanks véry much for sharing it in your blog.

Pozdravi, Pim.

Hi Pim, so glad you enjoyed the article! It was interesting to me to follow the local angle, rather than simply report the standard global analysis. This is part of my campaign to learn the language and the country better – and help other foreigners do so too! Mara